By Farid Nat

Engineering Analyst

Sustainable Investment Group (SIG)

When scientists first began testing refrigeration systems in the mid-1800’s, nobody suspected that this technology would have impacts on people’s daily lives for years to come, but they may have an even more significant role today. In fact, the need for refrigerants and access to air conditioning and food refrigeration have all vastly increased over the last 50 years and it will continue to grow. It is estimated that by 2030, 700 million new air conditioning units will become operational. Because of this it is important to understand some of the issues associated with many of the refrigerants we currently use.

When scientists first began testing refrigeration systems in the mid-1800’s, nobody suspected that this technology would have impacts on people’s daily lives for years to come, but they may have an even more significant role today. In fact, the need for refrigerants and access to air conditioning and food refrigeration have all vastly increased over the last 50 years and it will continue to grow. It is estimated that by 2030, 700 million new air conditioning units will become operational. Because of this it is important to understand some of the issues associated with many of the refrigerants we currently use.

What is a refrigerant?

Before we can begin to understand the problems with many refrigerants, it is important to understand exactly what a refrigerant is. A refrigerant is a chemical that has special properties that allow them to absorb or release heat easily under different conditions, and they are used to control temperatures or cool areas. In the refrigeration cycle, work is done on the refrigerant to either condense it to a liquid or evaporate it to a gas so that it can quickly adjust the temperature of the spaces being refrigerated. To do so, these refrigerants must have low boiling points and the ability to change phases without a lot of work. Because they need these special properties, only a certain variety of chemicals can be properly used. As a result, there are three main types of refrigerants that have been consistently used over time: Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), Hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), and Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). All three of these categories of refrigerants hold the important properties required to efficiently cool areas, but there are issues associated with these refrigerants.

What are the Issues with Refrigerants?

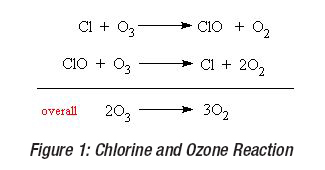

The main issue with many refrigerants is that they significantly contribute to climate change. While some refrigerants contribute to the depletion of the Ozone layer, increasing harmful ultraviolet radiation, others act as greenhouse gases with high global warming potential, or the ability to trap heat in the atmosphere. There has been a struggle in finding the right refrigerant that has a balance of a lower global warming potential and lower ozone depletion potential. For example,  CFCs and HCFCs both have chlorine and long lifecycles in the atmosphere, so when exposed to direct UV sunlight a chlorine atom is released. This chlorine then reacts with O3 (Ozone) molecules to form other molecules, removing Ozone from the atmosphere. Even worse, the cycle continues as the products of this reaction then react with oxygen molecules to separate the chlorine out, so it can again react with other ozone particles, continuously destroying ozone over time (1). To combat this, HFCs were developed as a safer alternative, since they don’t have any chlorine that depletes Ozone. However, HFCs are greenhouse gases that have long lifecycles in the atmosphere and contribute to keeping solar radiation and heat inside the Earth’s atmosphere. HFCs act as a barrier preventing solar radiation from escaping the atmosphere, and they are such great absorbers of heat that they have 1000 to 3000 times higher global warming potential than carbon dioxide change on average (2).

CFCs and HCFCs both have chlorine and long lifecycles in the atmosphere, so when exposed to direct UV sunlight a chlorine atom is released. This chlorine then reacts with O3 (Ozone) molecules to form other molecules, removing Ozone from the atmosphere. Even worse, the cycle continues as the products of this reaction then react with oxygen molecules to separate the chlorine out, so it can again react with other ozone particles, continuously destroying ozone over time (1). To combat this, HFCs were developed as a safer alternative, since they don’t have any chlorine that depletes Ozone. However, HFCs are greenhouse gases that have long lifecycles in the atmosphere and contribute to keeping solar radiation and heat inside the Earth’s atmosphere. HFCs act as a barrier preventing solar radiation from escaping the atmosphere, and they are such great absorbers of heat that they have 1000 to 3000 times higher global warming potential than carbon dioxide change on average (2).

What’s Been Done to Fight This?

In 1987 the United Nations created an international agreement on reducing ozone degradation called the Montreal Protocol on Ozone Depleting Substances, and it was the one of first pieces of environmental policy concerning refrigerants and climate change. The main goal of this protocol was to phase out the production and consumption of these  substances, mainly CFCs and HCFCs, as they were the most popular Ozone Depleting Substances. UN estimates show that the ozone layer will almost completely recover by the middle of this century because of the rapid phase out of ozone-depleting refrigerants. Then in 2015, once the global warming potential of HFCs became clear, the Kigali agreement was created as an amendment to the Montreal Protocol with the purpose of reducing the outputs of HFCs (3). Although the United States is yet to ratify or enforce the Kigali Agreement, it is still expected to prevent global average temperatures from increasing an additional .5 ℃ by 2100. It is also estimated that over 30 years, containing 87% of all leaked refrigerants could avoid emissions equal to 89.7 gigatons of carbon dioxide, and the Kigali Agreement itself could prevent 25 to 78 gigatons of carbon dioxide, which makes refrigerant management the best method for eliminating the most greenhouse gases in the atmosphere (4).

substances, mainly CFCs and HCFCs, as they were the most popular Ozone Depleting Substances. UN estimates show that the ozone layer will almost completely recover by the middle of this century because of the rapid phase out of ozone-depleting refrigerants. Then in 2015, once the global warming potential of HFCs became clear, the Kigali agreement was created as an amendment to the Montreal Protocol with the purpose of reducing the outputs of HFCs (3). Although the United States is yet to ratify or enforce the Kigali Agreement, it is still expected to prevent global average temperatures from increasing an additional .5 ℃ by 2100. It is also estimated that over 30 years, containing 87% of all leaked refrigerants could avoid emissions equal to 89.7 gigatons of carbon dioxide, and the Kigali Agreement itself could prevent 25 to 78 gigatons of carbon dioxide, which makes refrigerant management the best method for eliminating the most greenhouse gases in the atmosphere (4).

Ultimately, refrigerants are vital to many people’s daily lives worldwide, but they also have the potential to cause serious damage to the planet. Even though solid steps towards creating a solution to this issue are made through the Montreal Protocol and Kigali Agreement, there is still a lot of work to do to fully mitigate the impacts of these refrigerants. As a result, it will be important to consider the future of refrigerants and what new technologies may develop to combat these issues.

References

- https://www.lifegate.com/people/news/how-cfcs-destroy-ozone-layer

- https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/wp-content/uploads/legacy/Global/usa/binaries/2009/4/hfc-fact-sheet.pdf

- https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-kyoto-protocol/what-is-the-kyoto-protocol/kyoto-protocol-targets-for-the-first-commitment-period

- “Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming” Paul Hawken

Images

- Figure 1: http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/rzepa/mim/environmental/html/cfc.htm

- Figure 2: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/climate-change/differentiated-and-legally-binding-56094

© 2020 Sustainable Investment Group (SIG). All rights reserved.